If you're a woman in India, every day is a battle for existence; a battle to be heard in a society that has no use for your voice, least of all your words. To be a Dalit woman in India is to be doubly violated by the oppressive structures of both gender and caste.

In that sense, the poetry of Meena Kandasamy is revolutionary. Her writing is powerful, fearless and driven by her ardent desire to turn normative notions of the submissive woman on their heads. Kandasamy's writing is an act of relentless rebellion against Brahmanical patriarchy. In her poetry, we find the essence of a radical resistance against caste oppression and a clarion call to take up arms against the established order of the world.

Not only is she a poet par excellence, she has also published novels and translated several important works of prose and poetry from Tamil to English, such as the writings of Periyar, Thol. Thirumavalavan, and Tamil Eelam writers like Kasi Anandan, Cheran and VIS Jayapalan. She also writes columns for the Hindu and Outlook India, and has edited The Dalit, an alternative English magazine, from 2001-2002.

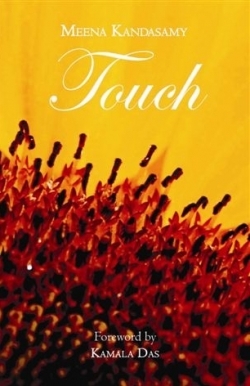

Kamala Das, one of India's foremost poets, in her foreword to Touch, Kandasamy's first poetry collection published in 2006, praises the poet as:

"Dying and then resurrecting herself again and again in a country that refuses to forget the

unkind myths of caste and perhaps of religion, Meena carries as her twin self, her shadow the

dark cynicism of youth that must help her to survive."

Kandasamy's poetry is a reflection of her own experiences as a Dalit woman, and of her politics. For her, her ideology influences her craft; her political belief is her greatest muse. Through her poetry, Kandasamy chips away at the dominance of the upper caste Hindu in defining the culture and traditions of all Hindus. Her feminist retellings of well known Hindu myths in her second poetry collection Ms Militancy are simultaneously a critique and subversion of the status quo. In the preface to the collection, Kandasamy writes,

"I work to not only get back at you, I actually fight to get back to myself. I do not write into patriarchy. My Maariamma bays for blood. My Kali kills. My Draupadi strips. My Sita climbs on to a stranger's lap. All my women militate. They brave bombs, they belittle kings. They take on the sun, they take after me."

In Indian society, a woman carries the dignity and honour of her family in her body. A woman's body is a receptacle of her purity and a site of immense violence as well. This strips her of any individuality and makes her a mere vessel that is meant to perform the roles forced upon her by society. In the first poem in Ms Militancy, Kandasamy articulates this position of the Indian woman. She writes,

"...I am torn apart

to contain the meanings of

family, race, stock, and caste

and form of existence

and station and fixed by birth

and I can take it no more."

As is evident, Kandasamy's artistic sensibilities are informed by her political beliefs. When Manisha Valmiki died in hospital on September 29 after being raped and brutally assaulted by upper-caste men in Hathras, Uttar Pradesh; Kandasamy expressed her outrage against India's systemic violence against women, and Dalit women in particular, by penning down a poem called Rape Nation. It captures the despair and helplessness that India's minorities feel as they fight for their existence in a centuries old social hierarchy rooted in violence and discrimination. We come across the line "This has happened before, this will happen again," five times in the poem- a reminder that while allies are only just realizing the effects of caste discrimination, India's Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi communities have been subjected to it all their lives. Kandasamy writes how sexual violence against women is deeply rooted in the history of this nation,

"What does the fire remember? The screams of satis

dragged to their husband's pyres and brides burnt alive;

the wails of caste-crossed lovers put to death,

the tongue-chopped shrieking of raped women.

This has happened before, this will happen again."

In Kandasamy's critique of and attacks against caste-patriarchy, we find her questioning the myths and stories that are etched into the fabric of Hindu culture. As these stories are passed down from one generation to the next, we also inherit the value systems that these stories espouse. By rewriting such stories, Kandasamy creates alternative narratives that subvert notions of the submissive Indian woman.

For example, in her poem Six Hours of Chastity, Kandasamy reinvents the story of Nalayani- the wife of Rishi Mudgal. In the original myth, Rishi Mudgal took on a diseased and deformed appearance in order to test his wife. Nalayani remained devoted to her husband despite everything and served him to the best of her abilities. Once, he expressed his desire to spend the night with a woman who sold sex in exchange for gold. Nalayani carried him in a basket and waited outside until he was done. It is said that Nalayani was reincarnated as Draupadi because she asked for a husband five times when she was given a boon for her chastity by Shiva.

In Kandasamy's version, however, as Nalayani waits outside the brothel while her husband is inside with another woman, she is mistaken for a prostitute by other men. For every hour of the night she spends waiting, a man comes and sleeps with her. There is the traveller, the spice vendor, the curious eighteen year old boy, the gambler and even the Brahmin priest. Nalayani, in fact, does not say anything at all and enjoys herself. In Kandasamy's retelling, Nalayani is allowed to exercise her agency, her sexual desires are fulfilled and she is not condemned to a life of utter servitude. In the end, Kandasamy writes,

"Six men, one for every hour of night.

And on the way home, as his weight cuts her

Shoulder blades, she laughs and cries and laughs

Again, at the lightness of her burden, the end of fate."

We need more poets like Kandasamy who do not shy away from speaking truth to power and who place the experiences of Dalit women at the very center of our culture. As she writes from the margins, she continues to militate against those who dominate the mainstream and control the lives of the marginalized. In her writing we find sparks of a revolution.